Different Kinds of MIDI Messages

A MIDI message is made up of an eight-bit status byte which is generally followed by one or two data bytes. There are a number of different types of MIDI messages. At the highest level, MIDI messages are classified as being either Channel Messages or System Messages. Channel messages are those which apply to a specific Channel, and the Channel number is included in the status byte for these messages. System messages are not Channel specific, and no Channel number is indicated in their status bytes.

Channel Messages may be further classified as being either Channel Voice Messages, or Mode Messages. Channel Voice Messages carry musical performance data, and these messages comprise most of the traffic in a typical MIDI data stream. Channel Mode messages affect the way a receiving instrument will respond to the Channel Voice messages.

Channel Voice Messages

Channel Voice Messages are used to send musical performance information. The messages in this category are the Note On, Note Off, Polyphonic Key Pressure, Channel Pressure, Pitch Bend Change, Program Change, and the Control Change messages.

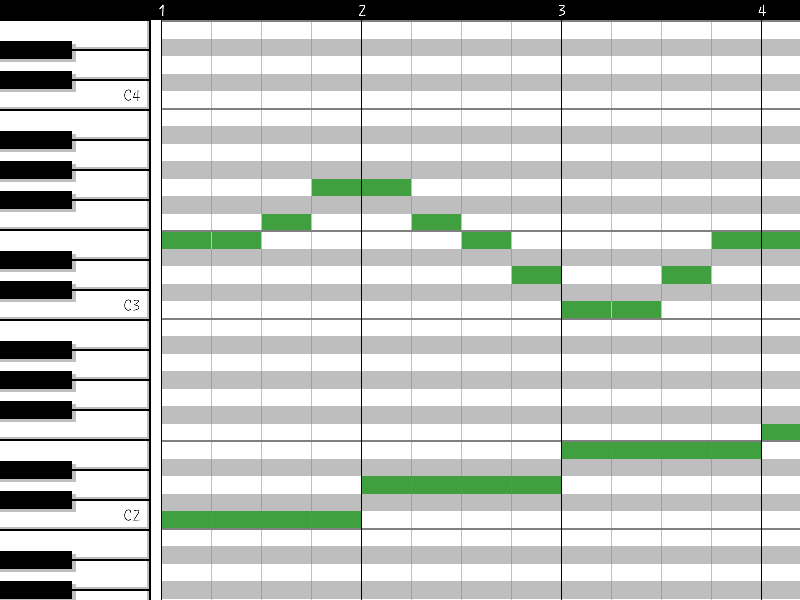

Note On / Note Off / Velocity

In MIDI systems, the activation of a particular note and the release of the same note are considered as two separate events. When a key is pressed on a MIDI keyboard instrument or MIDI keyboard controller, the keyboard sends a Note On message on the MIDI OUT port. The keyboard may be set to transmit on any one of the sixteen logical MIDI channels, and the status byte for the Note On message will indicate the selected Channel number. The Note On status byte is followed by two data bytes, which specify key number (indicating which key was pressed) and velocity (how hard the key was pressed).

The key number is used in the receiving synthesizer to select which note should be played, and the velocity is normally used to control the amplitude of the note. When the key is released, the keyboard instrument or controller will send a Note Off message. The Note Off message also includes data bytes for the key number and for the velocity with which the key was released. The Note Off velocity information is normally ignored.

Aftertouch

Some MIDI keyboard instruments have the ability to sense the amount of pressure which is being applied to the keys while they are depressed. This pressure information, commonly called “aftertouch”, may be used to control some aspects of the sound produced by the synthesizer (vibrato, for example). If the keyboard has a pressure sensor for each key, then the resulting “polyphonic aftertouch” information would be sent in the form of Polyphonic Key Pressure messages. These messages include separate data bytes for key number and pressure amount. It is currently more common for keyboard instruments to sense only a single pressure level for the entire keyboard. This “Channel aftertouch” information is sent using the Channel Pressure message, which needs only one data byte to specify the pressure value.

Pitch Bend

The Pitch Bend Change message is normally sent from a keyboard instrument in response to changes in position of the pitch bend wheel. The pitch bend information is used to modify the pitch of sounds being played on a given Channel. The Pitch Bend message includes two data bytes to specify the pitch bend value. Two bytes are required to allow fine enough resolution to make pitch changes resulting from movement of the pitch bend wheel seem to occur in a continuous manner rather than in steps.

Program Change

The Program Change message is used to specify the type of instrument which should be used to play sounds on a given Channel. This message needs only one data byte which specifies the new program number.

Control Change

MIDI Control Change messages are used to control a wide variety of functions in a synthesizer. Control Change messages, like other MIDI Channel messages, should only affect the Channel number indicated in the status byte. The Control Change status byte is followed by one data byte indicating the “controller number”, and a second byte which specifies the “control value”. The controller number identifies which function of the synthesizer is to be controlled by the message. A complete list of assigned controllers is found in the MIDI 1.0 Detailed Specification.

– Bank Select

Controller number zero (with 32 as the LSB) is defined as the bank select. The bank select function is used in some synthesizers in conjunction with the MIDI Program Change message to expand the number of different instrument sounds which may be specified (the Program Change message alone allows selection of one of 128 possible program numbers). The additional sounds are selected by preceding the Program Change message with a Control Change message which specifies a new value for Controller zero and Controller 32, allowing 16,384 banks of 128 sound each.

Since the MIDI specification does not describe the manner in which a synthesizer’s banks are to be mapped to Bank Select messages, there is no standard way for a Bank Select message to select a specific synthesizer bank. Some manufacturers, such as Roland (with “GS”) and Yamaha (with “XG”) , have adopted their own practices to assure some standardization within their own product lines.

– RPN / NRPN

Controller number 6 (Data Entry), in conjunction with Controller numbers 96 (Data Increment), 97 (Data Decrement), 98 (Non-Registered Parameter Number LSB), 99 (Non-Registered Parameter Number MSB), 100 (Registered Parameter Number LSB), and 101 (Registered Parameter Number MSB), extend the number of controllers available via MIDI. Parameter data is transferred by first selecting the parameter number to be edited using controllers 98 and 99 or 100 and 101, and then adjusting the data value for that parameter using controller number 6, 96, or 97.

RPN and NRPN are typically used to send parameter data to a synthesizer in order to edit sound patches or other data. Registered parameters are those which have been assigned some particular function by the MIDI Manufacturers Association (MMA) and the Japan MIDI Standards Committee (JMSC). For example, there are Registered Parameter numbers assigned to control pitch bend sensitivity and master tuning for a synthesizer. Non-Registered parameters have not been assigned specific functions, and may be used for different functions by different manufacturers. Here again, Roland and Yamaha, among others, have adopted their own practices to assure some standardization.

Channel Mode Messages

Channel Mode messages (MIDI controller numbers 121 through 127) affect the way a synthesizer responds to MIDI data. Controller number 121 is used to reset all controllers. Controller number 122 is used to enable or disable Local Control (In a MIDI synthesizer which has it’s own keyboard, the functions of the keyboard controller and the synthesizer can be isolated by turning Local Control off). Controller numbers 124 through 127 are used to select between Omni Mode On or Off, and to select between the Mono Mode or Poly Mode of operation.

When Omni mode is On, the synthesizer will respond to incoming MIDI data on all channels. When Omni mode is Off, the synthesizer will only respond to MIDI messages on one Channel. When Poly mode is selected, incoming Note On messages are played polyphonically. This means that when multiple Note On messages are received, each note is assigned its own voice (subject to the number of voices available in the synthesizer). The result is that multiple notes are played at the same time. When Mono mode is selected, a single voice is assigned per MIDI Channel. This means that only one note can be played on a given Channel at a given time.

Most modern MIDI synthesizers will default to Omni On/Poly mode of operation. In this mode, the synthesizer will play note messages received on any MIDI Channel, and notes received on each Channel are played polyphonically. In the Omni Off/Poly mode of operation, the synthesizer will receive on a single Channel and play the notes received on this Channel polyphonically. This mode could be useful when several synthesizers are daisy-chained using MIDI THRU. In this case each synthesizer in the chain can be set to play one part (the MIDI data on one Channel), and ignore the information related to the other parts.

Note that a MIDI instrument has one MIDI Channel which is designated as its “Basic Channel”. The Basic Channel assignment may be hard-wired, or it may be selectable. Mode messages can only be received by an instrument on the Basic Channel.

System Messages

MIDI System Messages are classified as being System Common Messages, System Real Time Messages, or System Exclusive Messages. System Common messages are intended for all receivers in the system. System Real Time messages are used for synchronization between clock-based MIDI components. System Exclusive messages include a Manufacturer’s Identification (ID) code, and are used to transfer any number of data bytes in a format specified by the referenced manufacturer.

System Common Messages

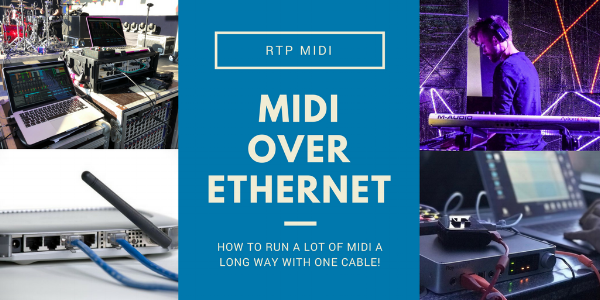

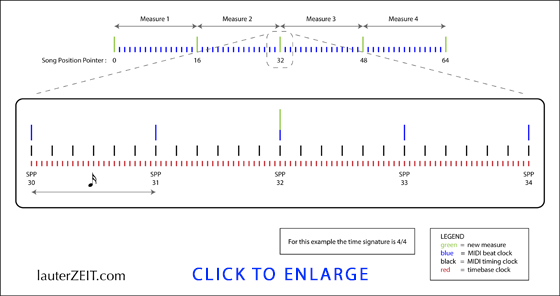

The System Common Messages which are currently defined include MTC Quarter Frame, Song Select, Song Position Pointer, Tune Request, and End Of Exclusive (EOX). The MTC Quarter Frame message is part of the MIDI Time Code information used for synchronization of MIDI equipment and other equipment, such as audio or video tape machines.

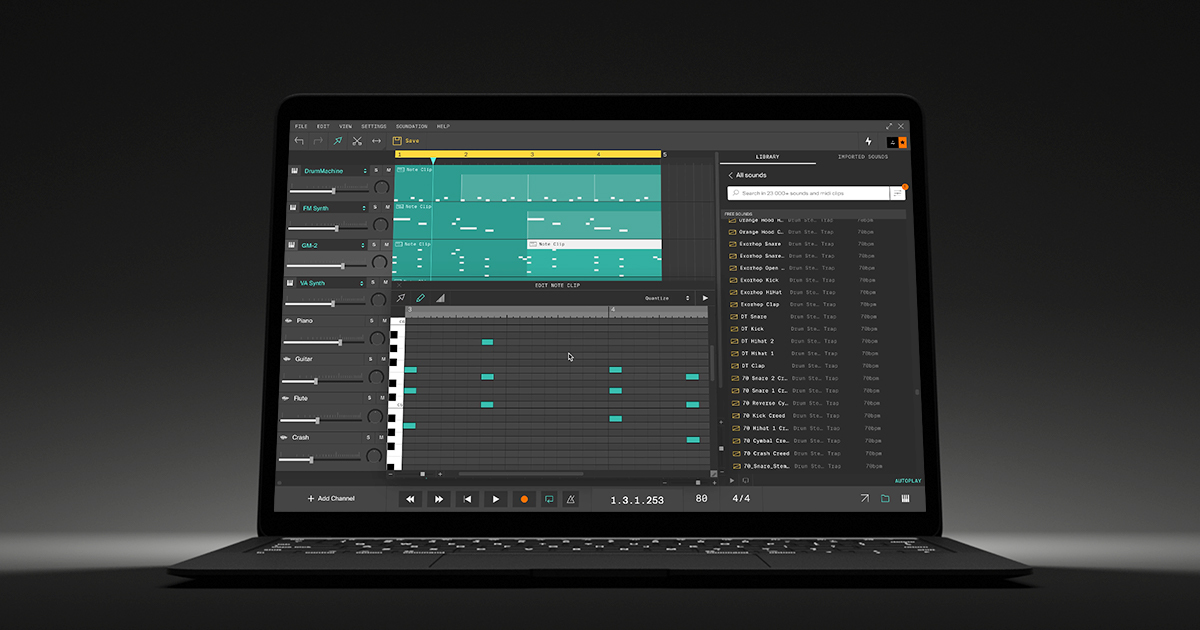

The Song Select message is used with MIDI equipment, such as sequencers or drum machines, which can store and recall a number of different songs. The Song Position Pointer is used to set a sequencer to start playback of a song at some point other than at the beginning. The Song Position Pointer value is related to the number of MIDI clocks which would have elapsed between the beginning of the song and the desired point in the song. This message can only be used with equipment which recognizes MIDI System Real Time Messages (MIDI Sync).

The Tune Request message is generally used to request an analog synthesizer to retune its’ internal oscillators. This message is generally not needed with digital synthesizers.

The EOX message is used to flag the end of a System Exclusive message, which can include a variable number of data bytes.

System Real Time Messages

The MIDI System Real Time messages are used to synchronize all of the MIDI clock-based equipment within a system, such as sequencers and drum machines. Most of the System Real Time messages are normally ignored by keyboard instruments and synthesizers. To help ensure accurate timing, System Real Time messages are given priority over other messages, and these single-byte messages may occur anywhere in the data stream (a Real Time message may appear between the status byte and data byte of some other MIDI message).

The System Real Time messages are the Timing Clock, Start, Continue, Stop, Active Sensing, and the System Reset message. The Timing Clock message is the master clock which sets the tempo for playback of a sequence. The Timing Clock message is sent 24 times per quarter note. The Start, Continue, and Stop messages are used to control playback of the sequence.

The Active Sensing signal is used to help eliminate “stuck notes” which may occur if a MIDI cable is disconnected during playback of a MIDI sequence. Without Active Sensing, if a cable is disconnected during playback, then some notes may be left playing indefinitely because they have been activated by a Note On message, but the corresponding Note Off message will never be received.

The System Reset message, as the name implies, is used to reset and initialize any equipment which receives the message. This message is generally not sent automatically by transmitting devices, and must be initiated manually by a user.

System Exclusive Messages

System Exclusive messages may be used to send data such as patch parameters or sample data between MIDI devices. Manufacturers of MIDI equipment may define their own formats for System Exclusive data. Manufacturers are granted unique identification (ID) numbers by the MMA or the JMSC, and the manufacturer ID number is included as part of the System Exclusive message. The manufacturers ID is followed by any number of data bytes, and the data transmission is terminated with the EOX message. Manufacturers are required to publish the details of their System Exclusive data formats, and other manufacturers may freely utilize these formats, provided that they do not alter or utilize the format in a way which conflicts with the original manufacturers specifications.

Certain System Exclusive ID numbers are reserved for special protocols. Among these are the MIDI Sample Dump Standard, which is a System Exclusive data format defined in the MIDI specification for the transmission of sample data between MIDI devices, as well as MIDI Show Control and MIDI Machine Control.