Three Hubs, One Revolution: How Silicon Valley, Japan, and Hamburg Shaped the Future of Polyphonic Synthesis and MIDI Software

From today’s perspective—where musicians can load dozens of virtual instruments inside a DAW and compose symphonies on a laptop—it is easy to forget that the foundations of modern electronic music were built in three different places, by three different communities, solving three different problems.

In the late 1970s and 1980s:

- In Silicon Valley, engineers created the first programmable polyphonic synthesizers.

- In Japan, manufacturers developed highly reliable, mass-market poly synths and helped give birth to MIDI.

- In Hamburg, Germany, musicians-turned-programmers created the software sequencers and workflows that defined the modern DAW.

These movements emerged independently, separated by geography and culture—but together they formed the foundation of today’s global music-technology ecosystem.

I. Silicon Valley in the Late 1970s: The Birth of the Programmable Polyphonic Synth

In the late 1970s, a unique blend of semiconductor innovation, early personal computing, and creative experimentation transformed Silicon Valley into the cradle of modern synthesizer design.

Key Figures & Companies

- Dave Smith (Sequential Circuits – Prophet-5)

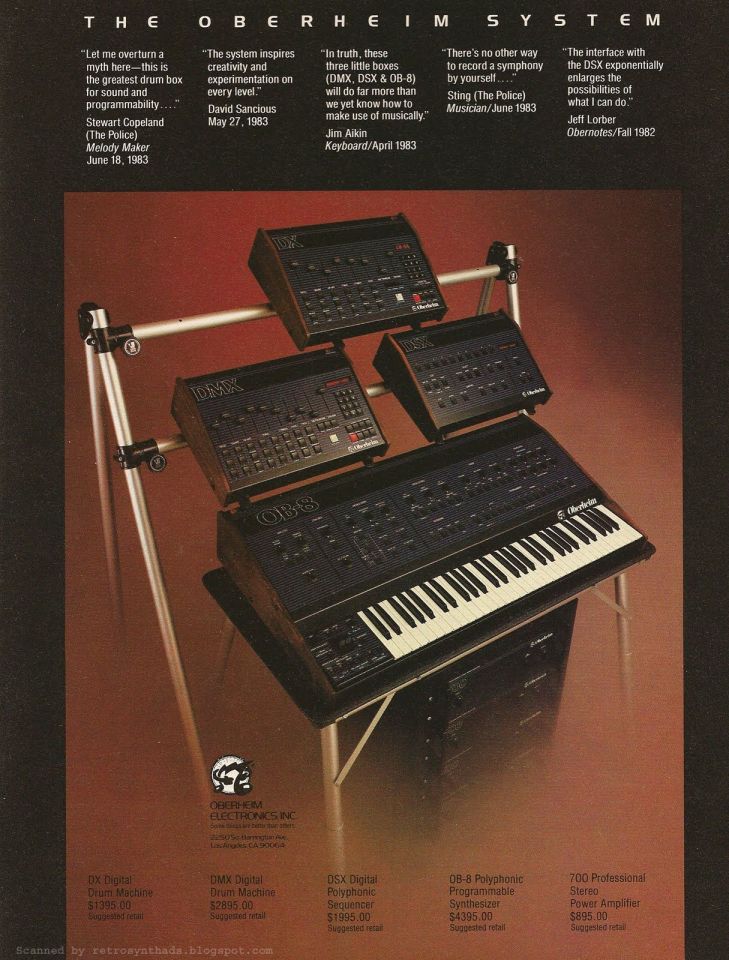

- Tom Oberheim (Oberheim OB-X, OB-Xa)

- Dave Rossum (E-mu Systems)

- Roger Linn (Linn Designs and The Linn Drum)

Silicon Valley in this period sat at the intersection of:

- early personal computing,

- semiconductor engineering, and

- experimental and popular music culture.

Musicians and engineers worked side-by-side with new microprocessors like the MOS Technology 6502 and Zilog Z80, making it possible to build instruments that:

- stored presets,

- tuned themselves,

- managed polyphony digitally, and

- offered consistent envelopes and LFOs.

The Prophet-5 (1978)

The Prophet-5 is widely considered the first fully programmable polyphonic synthesizer and one of the most influential instruments of the 20th century. By combining analog sound generation with digital control, it established the template for the modern polysynth.

Silicon Valley Culture

- Rapid prototyping and iteration

- Open exchange of engineering ideas

- Start-up mentality and risk-taking

- A strong overlap between computing and music engineering

Silicon Valley changed the sound of electronic music.

II. Japan in the Late 1970s to Early 1980s: Precision, Mass Production, and the Road to MIDI

While Silicon Valley produced the first breakthrough programmable polyphonic synths, Japanese companies scaled and refined them, creating reliable instruments that defined entire genres.

Key Figures & Companies

- Ikutaro Kakehashi (Roland – Jupiter and Juno series)

- Tadao Kikumoto (Roland- TR808)

- Tsutomu Katoh (Korg Polysix, Mono/Poly, M1)

- Tetsuo Nishimoto (Yamaha CS series, DX 7)

Japan Democratized the Polyphonic Synth

Japanese manufacturers excelled at:

- cost-efficient component selection,

- mass production,

- designing for reliability, and

- creating intuitive panel layouts.

Instruments like the Roland Juno-60 and the Korg Polysix brought polyphonic synthesis to a much wider audience than boutique American instruments could reach on their own. Then the Yamaha DX7, Roland D-50, and Korg M1 added MIDI to the mix.

Japan Pushed Technical Stability

Japanese poly synths became known for:

- excellent tuning stability,

- robust keyboards,

- precise envelopes, and

- dependable build quality.

This made electronic instruments truly viable on stage and in commercial studios worldwide.

Japan Helped Shape MIDI Itself

The collaboration between Ikutaro Kakehashi (Roland) and Dave Smith (Sequential Circuits) directly contributed to the creation of the MIDI standard in 1983. Japan’s role was not only in manufacturing instruments but also in establishing the protocol that allowed them to communicate.

Japan changed the accessibility, reliability, and standardization of electronic instruments.

III. Hamburg in the Late 1980s: The Rise of MIDI Sequencing and the Birth of the DAW

While Silicon Valley and Japan were perfecting polyphonic synthesizers, a very different revolution took shape a decade later in Hamburg, Germany.

Key Figures & Companies

- Gerhard Lengeling (C-Lab Creator, Notator → Logic)

- Chris Adam (C-Lab / Emagic co-founder)

- Charlie Steinberg (Steinberg – Pro-24, Cubase)

- Manfred Rürup (Steinberg co-founder)

Why Hamburg?

Hamburg in the 1980s featured:

- a strong classical and jazz tradition,

- a thriving pop and rock studio scene,

- experimental electronic musicians, and

- a new generation of programmer-musicians.

This made it a fertile ground for new kinds of music software that blended musical and technical expertise.

The Atari ST: Catalyst for Software Innovation

The Atari ST, introduced in 1985, came with built-in MIDI ports, a responsive graphical user interface, and an affordable price point. It quickly became the European musician’s computer of choice and the platform on which Hamburg’s developers built the next generation of music tools.

You can find that intriguing story of why the Atari and had MIDI Ports here.

https://midi.org/craig-andertons-brief-history-of-midi

C-Lab Creator / Notator

C-Lab developed Creator and later Notator, sequencers renowned for:

- pattern-based composition,

- real-time quantization and MIDI transforms,

- a hybrid of notation and MIDI editing, and

- advanced MIDI processing concepts that would later influence Logic’s Environment.

Gerhard Lengeling’s work at C-Lab would eventually evolve into Notator Logic, then Logic, and later Logic Pro after the formation of Emagic and Apple’s acquisition.

Steinberg Pro-24 → Cubase

Steinberg introduced Pro-24 and later Cubase, whose track-based Arrange Window became a model for modern DAW timelines. Cubase’s graphical approach to MIDI editing set standards that many later DAWs would follow.

In later years, Steinberg would introduce VST (Virtual Studio Technology) and ASIO, extending Hamburg’s influence from MIDI sequencing into audio processing and low-latency software design.

Hamburg changed how music is composed, arranged, and edited.

IV. How These Three Movements Differed — and Why They Converged

| Aspect | Silicon Valley (1970s) | Japan (Late 70s–Early 80s) | Hamburg (Late 1980s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Hardware invention | Mass production & reliability | Software & workflow |

| Innovation Type | Analog + microprocessor integration | High-quality engineering & affordability | MIDI sequencing, editing, DAW structures |

| Key Output | Prophet-5, OB-X, early ICs | Juno, Jupiter, Polysix, DX series,DX7, D-50, M1 | Creator, Notator, Cubase |

| Driving Culture | Silicon start-up mindset | Precision manufacturing & export | Composer-programmer hybrid |

| Problem Solved | “How do we make new sounds?” | “How do we make synths stable and accessible?” | “How do we organize and edit electronic music?” |

These three movements were not competitors; they were complementary revolutions that formed the backbone of today’s tools.

V. The Connecting Thread: MIDI

MIDI provided the bridge between:

- American synthesizer innovation,

- Japanese manufacturing and standardization, and

- European sequencing and software design.

Without Silicon Valley’s programmable synths, Japan’s market reach, and Hamburg’s sequencing innovations, MIDI would never have become the universal language of electronic music.

Each region carried one piece of the puzzle:

- The U.S. created the instrumental vocabulary.

- Japan made the instruments affordable and standardized.

- Germany created the compositional and editing environment.

All three were essential for the DAW-centric workflows we now take for granted.

VI. Long-Term Impact: The Foundation of Modern Music Production

By the early 1990s:

- Synthesizers had migrated into workstations and ROMplers.

- MIDI sequencing had evolved into full-fledged DAWs.

- Software began absorbing synthesis via plugins and virtual instruments.

- Reliable Japanese synths coexisted with newer soft synths.

- Polyphonic analog circuits inspired modern virtual analog designs.

- Logic and Cubase emerged directly from the Hamburg development lineage.

Today’s essential tools—DAWs, virtual instruments, MIDI editing, plugin ecosystems—owe their origins to these three regional revolutions.

Conclusion: Three Destinations, One Journey

The late-1970s synthesizer revolution in Silicon Valley, the Japanese wave of mass production and standardization, and the late-1980s Hamburg software revolution were separate in geography, timing, and culture—but deeply unified in purpose.

Each movement solved the next problem in the chain:

- Silicon Valley invented the modern electronic instrument.

- Japan perfected and democratized it.

- Hamburg gave musicians the software tools to organize and express it.

Together, they transformed music creation from a hardware-bound discipline into the flexible, expressive, digital medium that defines the industry today.