How to Find MIDI Sequencer “Gotchas”

Fix those little “gotchas” before they make it into the final mix

by Craig Anderton

MIDI sequencing is wonderful, but it’s not perfect—and sometimes, you’ll be sandbagged by problems like false triggers (e.g., what happens when you brush against a key accidentally), having two different notes land on the same beat when quantized, voice-stealing that cuts off notes abruptly, and the like. These glitches may not be obvious when other instruments are playing, but they nonetheless can muddy up a piece or even mess up the rhythm. Just as you’d “proof” your writing, it’s a good idea to “proof” sequenced tracks.

Begin by listening to each track in isolation; this reveals flaws more readily than listening to several tracks simultaneously. Headphones can also help, as they may reveal details you’d miss over speakers. As you listen, also check for voice-stealing problems caused by multi-timbral soft synths running out of voices. Sometimes if notes are cut off, merely changing note durations to prevent overlap—or deleting one note from a chord—will solve the problem. But you may also need to dig deeper into some other issues, such as . . .

NOTES WITH ABNORMALLY LOW VELOCITIES OR DURATIONS

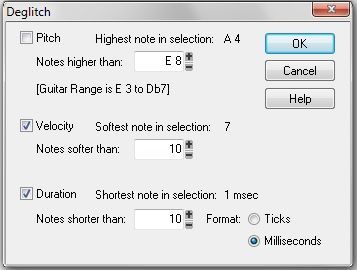

Even if you can’t hear these notes, they still use up voices. They’re easy to find in an event list editor, but if you’re in a hurry, do a global “remove every note with a velocity of less than X” (or for duration, “with a note length less than X ticks”) using a function like Cakewalk Sonar’s DeGlitch option (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Sonar’s DeGlitch function is deleting all notes with velocities under 10 and durations under 10 milliseconds.

Note that most MIDI guitar parts benefit greatly from a quick cleanup of notes with low velocities or durations.

UNWANTED AFTERTOUCH (CHANNEL PRESSURE) DATA

If your master controller generates aftertouch (pressure) but a patch isn’t programmed to use it, you’ll be recording lots of data that serves no useful purpose. When driving hardware synths, this can create timing issues and there may even be negative effects with soft synths if you switch from a sound that doesn’t recognize aftertouch to one that does.

Note that there are two types of aftertouch—channel aftertouch, which generates one message that correlates to all notes being pressed, and polyphonic aftertouch, which generates individual messages for each note being pressed. The latter sends a lot of data down the MIDI stream, but as there are few keyboard controllers with polyphonic aftertouch, it’s unlikely you’ll encounter this problem.

Steinberg Cubase’s Logical Editor (Fig. 2) is designed for removing specific types of data, and one useful application is removing unneeded aftertouch data.

Fig. 2: In this basic application of Cubase’s Logical Editor, all aftertouch data is being removed.

Note that many recording programs disable aftertouch recording as the default, but if you enable it at some point, it may stay enabled until you disable it again.

OVERLY WIDE DYNAMIC VARIATIONS

This can be a particular problem with drum parts played from a keyboard—for example, some all-important kick drum hits may be much lower than others. There are two fixes: Edit individual notes (accurate, but time-consuming), or use a MIDI edit command that sets a minimum or maximum velocity level, like the one from Sony Acid Pro (Fig. 3). With pop music drum parts, I often limit the minimum velocity to around 60 or 70.

Fig. 3: Sony’s Acid Pro makes it easy to restrict MIDI dynamics to a particular range of velocity values.

DOUBLED NOTES

If you “bounce” a key (or drum pad, for that matter) when playing a note, two triggers for the same note can end up close to each other. This is also very common with MIDI guitar. Quantization forces these notes to hit on the same beat, using up an extra voice and producing a flanged/delayed sound. Listening to a track in isolation usually reveals these flanged notes; erase one (if two notes hit on the same beat, I generally erase the one with the lower velocity value). Some programs offer an edit function that deletes duplicates automatically, such as Avid Pro Tools’ Delete Duplicate Notes function (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Pro Tools has a menu item dedicated specifically to eliminating duplicate MIDI notes.

NOTES OVERLAP WITH SINGLE-NOTE LINES

This applies mostly to bass and wind instruments. In theory, with single-note lines you want one note to end before another begins. Even slight overlaps make the part sound more mushy (bass in particular loses “crispness”) but what’s worse, two voices will briefly play where only one is needed, causing voice-stealing problems. Some programs let you fix overlaps as a Note Duration editing option.

However note that with legato mode, you do want notes to overlap. With this mode, a note transitions smoothly into the next note, without re-triggering an envelope when the next note occurs. Thus in a series of legato notes, the envelope attack occurs only for the first note of the series. If the notes overlap without legato mode selected, then you’ll hear separate articulations for each note. With an instrument like bass, legato mode can simulate sliding from one fret to another to change pitch without re-picking the note.

Craig Anderton is an Executive Vice-President at Gibson Brands, and Editorial Director of Harmony Central. He has played on, mixed, or produced over 20 major label releases (as well as mastered over a hundred tracks for various musicians), and written over a thousand articles for magazines like Guitar Player, Keyboard, Sound on Sound (UK), and Sound + Recording (Germany). He has also lectured on technology and the arts in 38 states, 10 countries, and three languages. This article is reprinted with the express written permission of HarmonyCentral.