Dave Oppenheim, Opcode Systems, and the Foundations of the Modern DAW

As the MIDI community gathers for the 2026 NAMM Show, The MIDI Association proudly recognizes Dave Oppenheim with a MIDI Lifetime Achievement Award. As the founder and principal architect of Opcode Systems, Inc., Oppenheim helped define what it means to create music with a computer. His work on MIDI sequencing, virtual studio infrastructure, and integrated audio–MIDI production set the stage for the modern digital audio workstation.

Youtube Summary Video

Opcode’s legacy, however, is also the story of strong collaboration and complementary talents. Alongside Oppenheim’s visionary engineering stood Chris Halaby, who joined Opcode in the late 1980s and served as President and CEO through the company’s most significant years of growth. Together, Oppenheim and Halaby built Opcode from a small, experimental startup into one of the most influential music software and hardware companies of the 1990s.

From early Macintosh sequencers to Vision, Studio Vision, OMS, Galaxy, and professional MIDI hardware, Opcode helped invent the workflows that musicians around the world now take for granted. This award honors not only Oppenheim’s profound contributions, but also the broader history of Opcode and the people who helped bring his ideas into studios everywhere.

Founding Opcode: From Experiment to Company

Opcode Systems was founded in 1985 in Palo Alto, California, at a moment when the Macintosh computer was just beginning to show its potential as a creative tool. Dave Oppenheim, a Stanford graduate and accomplished musician, saw that the Mac’s graphical interface, combined with MIDI, could transform how musicians composed and recorded music. He began developing one of the earliest commercial MIDI sequencers for the Mac, initially known as MIDIMAC.

In these formative years, Opcode’s focus was clear: use the Macintosh to give musicians a more direct and expressive relationship with their instruments and ideas. Early products included MIDI interfaces and sequencing tools that allowed the Mac to become the “central nervous system” of a studio.

The company’s first public showings quickly drew attention from forward-thinking artists and composers who were eager to move beyond hardware-only workflows.

As the company grew, Opcode’s leadership evolved as well. In 1987, Chris Halaby became President and Chief Executive Officer. Under Oppenheim’s technical direction and Halaby’s business leadership, Opcode expanded its product line, its staff, and its global presence. This partnership—engineering innovation guided by clear strategic vision—would define Opcode’s most influential decade.

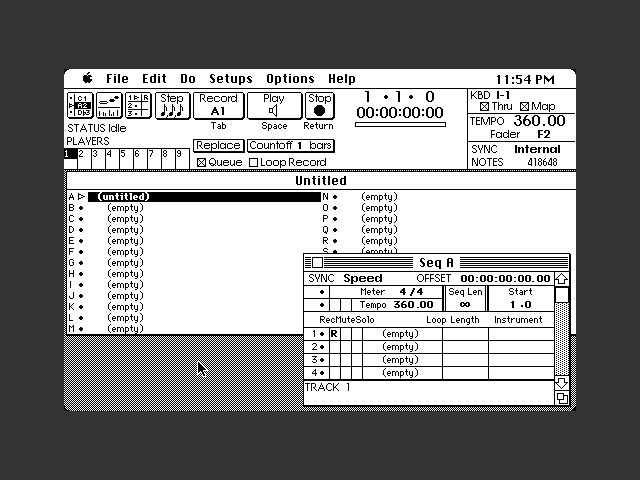

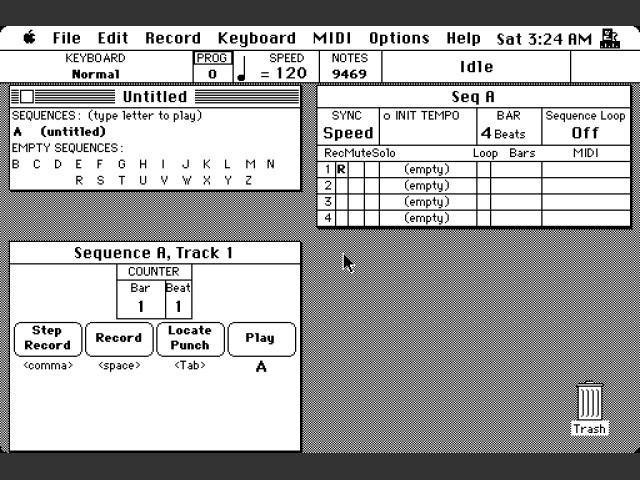

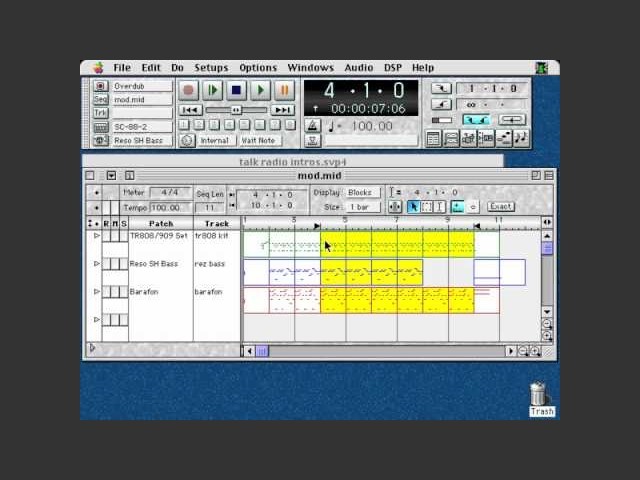

Vision: Redefining MIDI Sequencing on the Macintosh

Opcode’s breakthrough sequencing platform arrived with the release of Vision in 1989. More than just an update to the earlier MIDIMAC Sequencer, Vision represented a new way of thinking about MIDI composition and editing. At a time when many sequencers still relied heavily on event lists or step-time entry, Vision placed emphasis on:

- Graphical editing that mapped musical ideas onto intuitive visual structures,

- Object-based workflows where phrases and sections could be moved, copied, and reshaped like building blocks,

- Real-time recording and editing that allowed performance and refinement to happen in the same environment, and

- Musician-friendly interface design that kept technical complexity behind powerful yet approachable tools.

Vision quickly became a favorite among film and television composers, pop and rock producers, and experimental musicians. Its reputation for stability, musicality, and depth helped solidify the Macintosh as the preferred platform for professional music production.

Under Halaby’s stewardship, Opcode expanded Vision’s reach with simplified versions such as EZ Vision and MusicShop, bringing advanced sequencing concepts to a wider audience while maintaining a clear upgrade path to the flagship product.

OMS: Building a Virtual MIDI Studio

As MIDI studios evolved in the late 1980s and early 1990s, musicians found themselves juggling multiple synthesizers, sound modules, drum machines, and interfaces. Each application had its own way of dealing with devices, patch lists, and synchronization. Oppenheim recognized that what musicians needed was not just another utility, but a virtual MIDI studio layer that sat beneath all their music software.

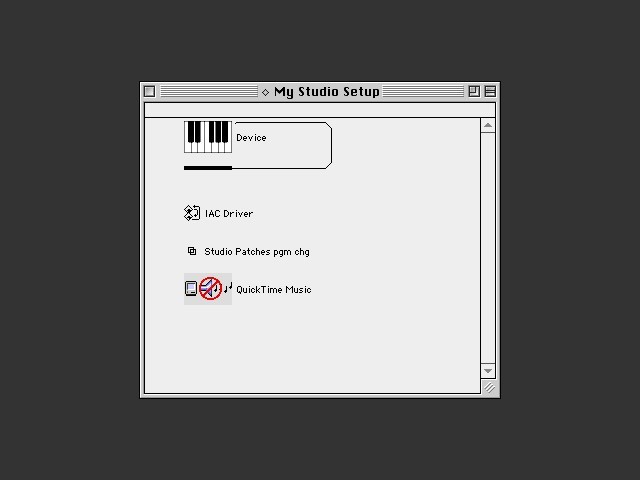

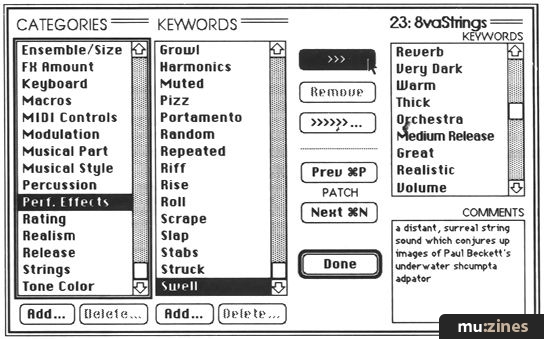

The result was the Opcode MIDI System (OMS), released in 1990. OMS allowed users to describe their entire MIDI setup visually—naming devices, assigning ports and channels, defining patch banks—and then made that information available system-wide. Multiple applications could share the same configuration, and patch names from librarian software such as Galaxy could appear directly in Vision and Studio Vision.

OMS became the de facto standard MIDI infrastructure on the Macintosh for much of the 1990s. It embodied Oppenheim’s belief in interoperability and Halaby’s commitment to building a robust ecosystem rather than isolated products. The conceptual framework of OMS would later echo in CoreMIDI and other system-level MIDI solutions that followed.

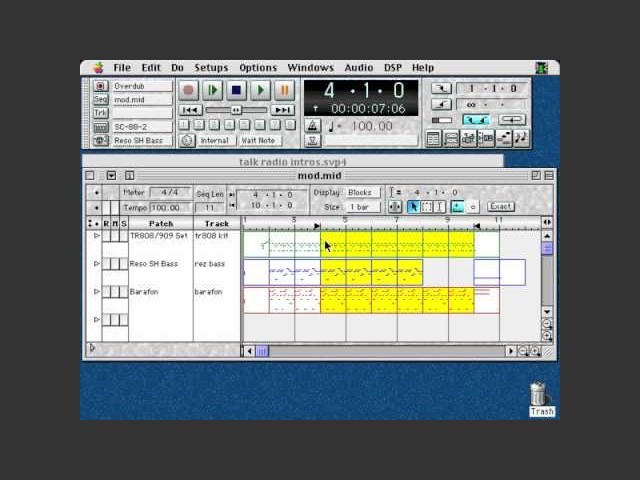

Studio Vision: The First Integrated MIDI + Audio Workstation

Perhaps Opcode’s most historically significant contribution came with the release of Studio Vision in 1990. Built on the foundation of Vision, Studio Vision was the first commercially available product to integrate MIDI sequencing and digital audio recording on a single, unified timeline on a mass-market personal computer.

With Studio Vision, musicians could:

- Record and edit MIDI and audio side by side,

- Align vocal and instrument recordings with sequenced parts,

- Perform non-destructive edits on digital audio, and

- Work with Digidesign hardware for professional-quality recording and playback.

This hybrid environment foreshadowed the modern DAW in almost every respect. Whether used for pop production, film scoring, sound design, or experimental composition, Studio Vision gave artists the ability to treat MIDI and audio as equal partners in a single creative space. Oppenheim’s technical leadership and Halaby’s strategic direction together ensured that Studio Vision reached studios around the world at a critical moment in the industry’s transition from tape to digital.

Galaxy, Hardware, and the Opcode Ecosystem

Opcode’s influence extended beyond sequencing and virtual studio infrastructure. The company developed one of the most comprehensive patch librarian systems of its time with Galaxy and its associated editors. Galaxy allowed users to store, organize, and edit sounds for a wide range of synthesizers and sound modules, integrating tightly with Vision and Studio Vision so that patch names and structures could flow seamlessly between applications.

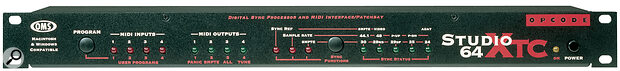

On the hardware side, Opcode produced a respected line of MIDI interfaces and related products, including the Studio 3, Studio 4, Studio 5, Studio 64X, and later USB-based devices.

MIDI To The Max

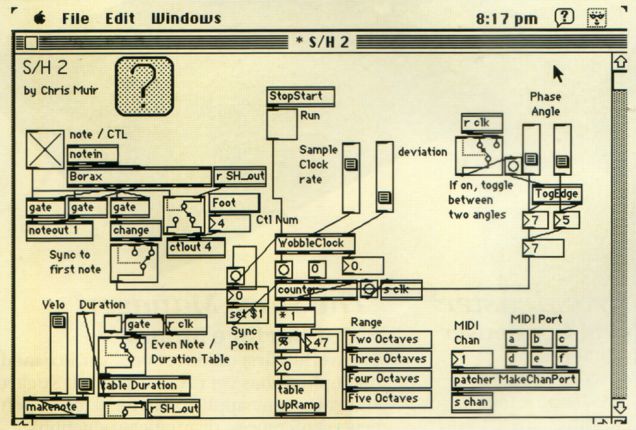

Not to be forgotten in the Opcode story is that they were the first home for Max an object-orientated MIDI programming language named after avant garde composer Max V. Mathews.

Max began in the mid-1980s at IRCAM, where Miller Puckette created it as an innovative visual programming environment for interactive computer music, allowing composers and researchers to build real-time signal-processing and performance systems without traditional coding.

Its power quickly drew interest beyond research circles, and in the early 1990s Opcode Systems acquired the commercial rights, bringing Max to a broader community of musicians and developers while integrating it with popular MIDI and digital audio workflows of the era.

When Opcode closed, David Zicarelli—who had long collaborated on Max’s development—founded Cycling ’74 and re-launched the software, expanding it with MSP for audio processing and later Jitter for video, establishing Max as a cornerstone of experimental media arts and advanced music technology.

In the 2010s, Max deepened its industry reach through an unprecedented integration with Ableton Live, resulting in Max for Live—an embedded version that allows users to build custom instruments, audio effects, sequencers, and MIDI tools directly inside Live’s workflow.

Today, this lineage of openness and interoperability continues as Max plays a key role in initiatives like Connect Through MIDI, where its flexible environment enables rapid prototyping, educational tools, and accessibility-focused applications that showcase the expressive possibilities of modern MIDI.

These interfaces became mainstays in professional studios, known for their timing accuracy and robust build quality. The acquisition of Music Quest in the mid-1990s further broadened Opcode’s hardware portfolio, particularly for Windows users.

Under Halaby’s leadership, Opcode grew to dozens of employees and a broad user base, while Oppenheim and the engineering team continued to push the boundaries of what was possible with MIDI and digital audio on personal computers. Together, they built not just individual products, but a complete ecosystem that spanned software, hardware, and studio infrastructure.

Acquisition, Transition, and Lasting Influence

In 1998, Opcode Systems was acquired by Gibson. While the merger initially seemed to promise new resources and reach, changing market conditions, competing platforms, and strategic realignments ultimately led to the discontinuation of Opcode products the following year. Even so, the ideas pioneered at Opcode never disappeared.

It’s interesting to note that Calkwalk was also purchased by Gibson at around the same time and suffered a similar fate.

Oppenheim’s architectural vision—integrated timelines, unified MIDI device management, hybrid audio–MIDI workflows—continues to shape every major DAW in use today. Halaby’s work in guiding Opcode’s growth, championing musician-focused design, and supporting an ecosystem approach helped cement the company’s influence during the critical years when computer-based music production was taking form.

The conceptual threads running from Vision and Studio Vision can be traced through Logic Pro, Cubase, Pro Tools, and many other platforms. OMS anticipated system-level MIDI frameworks. Galaxy and Opcode’s interfaces prefigured tightly integrated editor–librarian and hardware solutions that are now standard practice. For many musicians who came of age in the 1990s, Opcode was not just a brand; it was the environment in which they learned what digital music production could be.

Chris Halaby — What He’s Doing Now

- Chris Halaby is currently CEO of KVR Audio, a leading online community and information hub for music technology, software, and plug-ins.

- He joined the board of the Bob Moog Foundation, supporting its mission to preserve synthesizer history and promote music-technology education.

- Given KVR Audio’s focus — user communities, plug-in marketplaces, music-software news — Halaby remains deeply connected to the broader world of music technology, including MIDI tools, plugin development, and software/hardware integration.

In short: Halaby continues to play an active role in music-software and tech communities. While his current work is not primarily about developing sequencers or interfaces, through KVR Audio and the Moog Foundation he remains close to the pulse of MIDI, virtual instruments, and music-tech culture.

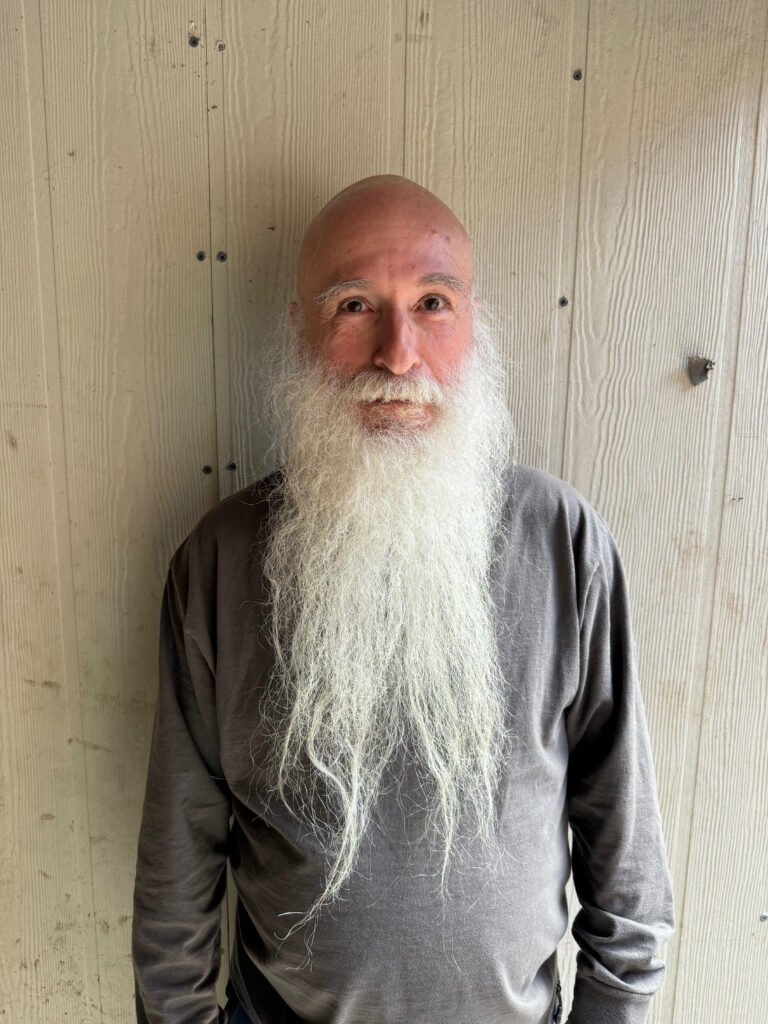

Dave Oppenheim’s continuing MIDI Journey

Recently, Dave has been working for Avid on their MIDI implentation. Avid is a current MIDI Association member and Dave has participated in many MIDI 2.0 meetings.

Celebrating Dave Oppenheim and the Opcode Legacy

In honoring Dave Oppenheim with the 2026 MIDI Association Lifetime Achievement Award, we celebrate a visionary whose technical insight and musical sensitivity helped define an era. We also acknowledge the vital contributions of Chris Halaby and the many engineers, designers, writers, testers, and support staff who made Opcode Systems such a powerful force in the evolution of music technology.

Opcode’s story is a reminder that the tools we use today are built on the ideas and dedication of people who were willing to imagine a different future for music creation. Dave Oppenheim’s work at Opcode Systems opened that future, showing the world how computers, MIDI, and digital audio could come together as a single, expressive instrument.

The MIDI Association proudly recognizes Dave Oppenheim and the legacy of Opcode Systems, Inc. for their foundational contributions to the art and technology of music creation. Their innovations continue to echo in studios, classrooms, and stages around the world.