Charlie Steinberg, Steinberg Media Technologies, and the Evolution of the Virtual Studio

When Charlie Steinberg receives the 2026 MIDI Association Lifetime Achievement Award at the NAMM Show, the recognition celebrates a musician, engineer, and inventor whose work helped shape the entire era of computer-based music creation.

As co-founder of Steinberg Media Technologies, Steinberg’s innovations—from early MIDI sequencing to today’s industry standards—transformed how musicians interact with technology.

From gigging musician to software pioneer

Karl “Charlie” Steinberg was a working musician and audio engineer long before his name appeared on software splash screens. In the late 1970s he played keyboards in German rock band Törner Stier Crew, who won first prize from the Deutsche Phono-Akademie (precursor to the Echo awards) and appeared on WDR’s Rockpalast.

In the early ’80s he was also behind the console, engineering and mixing records for artists associated with the Neue Deutsche Welle scene and recording singer Inga Rumpf’s album Liebe. Leiden. Leben. at Wilster Studio in 1984.

00:02:10 @charlie

That’s correct. Yeah.

If my memory serves me well, it was about 1981 when I met Manfred Ruerup (co-founder of Steinberg Research, today Steinberg Media technologies) at the Delta Studio in Wilster, Germany. There, I recorded 3 albums with my former band Toerner Stier Crew, and as the studio owners realized that I had learned to twiddle them desk knobs somewhat reasonably, they offered me a job as an engineer. I stayed there for more than a year and mixed and co-produced several records.

I didn’t know Manfred and at that time, the the German record companies were looking desperately for anything that had silly German lyrics, basically. And, you know, and all the 99 LuftBalloons and all that stuff at that time.

And he had made a a demo, which was really funny, And so they said, you go to the studio and make it better. And then they hired me as an engineer. So that’s how I got to know Manfred who was working at AmTown in Hamburg (a big music store in Hamburg) so he always brought the latest gear with him, which was really great.

And we hooked everything together. Anything that would put out a clock would be in there, you know? It was amazing. It’s great times.

And one day, he brought with him an American keyboard magazine which was kind of a rarity in in Germany.

And in there, the the MIDI protocol was described, you know, with seventh bit which makes a status and all that stuff.

And I looked at that. I had just started with, computers, and I said, you know, we could record that and do what the drum machines at that time did. Have patterns, quantization, and that’s where the yeah, the fun started.

Charlie Steinberg

Interview with The MIDI Association

That dual identity—musician and engineer—would define his life’s work. When MIDI appeared in 1983, Steinberg and fellow Hamburg musician Manfred Rürup immediately saw its potential. Rürup was working part-time at the Amptown keyboard shop, where the brand-new MIDI standard was just arriving on synths from Yamaha, Roland, Sequential, Korg, and others.

According to later recollections from colleagues, Steinberg and Rürup were initially frustrated by one of the first commercial MIDI sequencers for the Commodore 64, and decided they could build something better for their own studio. That DIY impulse would eventually change music production worldwide.

Steinberg Research and the birth of computer MIDI sequencing

In 1984, working out of Rürup’s Hamburg apartment, the pair formally founded Steinberg Research (now Steinberg Media Technologies). Their first commercial product was the MIDI Multitrack Sequencer for the Commodore 64, sold together with a home-built MIDI interface called the Steinberg Research Interface. Only around 50 systems were sold, but they proved the concept: a home computer could behave like a multi-track MIDI recorder.

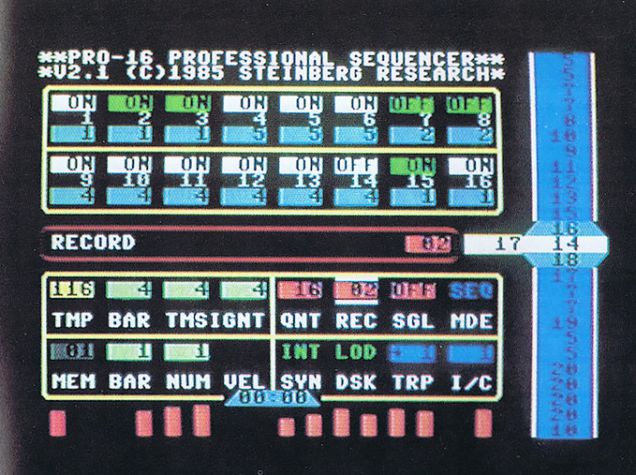

Steinberg followed quickly with Pro-16 for the C64, again largely coded by Charlie himself. The name reflected the tape-machine metaphor: 16 MIDI “tracks” instead of 16 tape tracks.

A new interface, CARD 32, added multiple MIDI outs, tape sync, and even an EPROM version of Pro-16 that booted instantly when you powered up the computer—radical convenience in the mid-’80s.

In 1985 the company hired developer Werner Kracht, who spent 1986 building Pro-24 for the Atari ST. The timing was perfect: the Atari ST famously shipped with built-in MIDI ports, and Pro-24’s 24 “tape” tracks turned the affordable home computer into a serious sequencing powerhouse. Very quickly, Steinberg’s software became a standard tool for European studios, pop producers, and the emerging electronic-dance scene.

He was working with another company and then he came to us and it was great because he could concentrate on the Atari, which was very hard to handle. There was yay size three books of documentation which weren’t really related to the actual unit.

Because they had a different system. It was derived from what was written in the book.

So it was a tough piece of work that he did, but he did it, and it was a great machine and it had MIDI in it.

It had a, graphical interface like a Mac.

Macs were kind of, you know, unaffordable.In Germany. They were so expensive. Only the graphics people would have that. Yeah. And so I worked then on the MROS, And, yeah, that’s how it came together.

Charlie Steinberg

Interview with The MIDI Association

During this interview, we talked about the Atari and why it had MIDI Ports. You can find that intriguing story here.

https://midi.org/craig-andertons-brief-history-of-midi

The Arrival of Cubase and the DAW Revolution

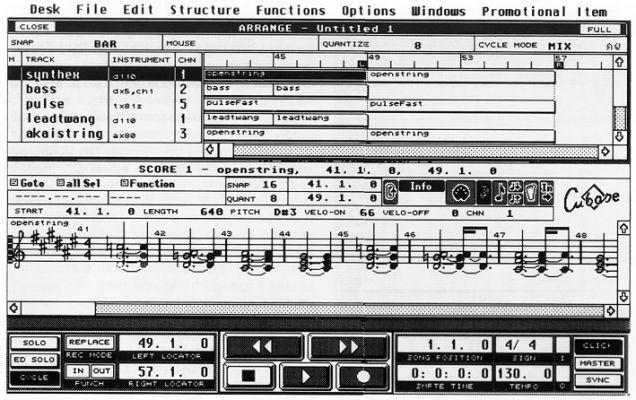

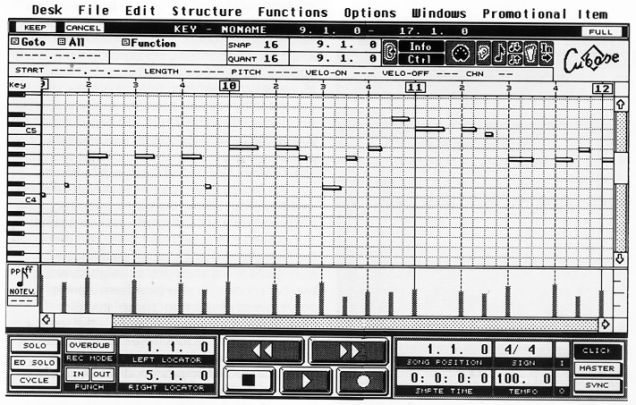

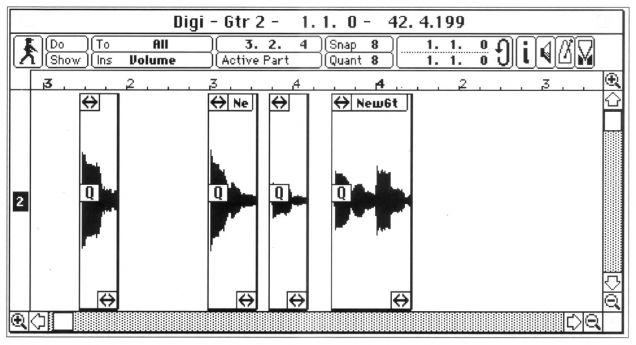

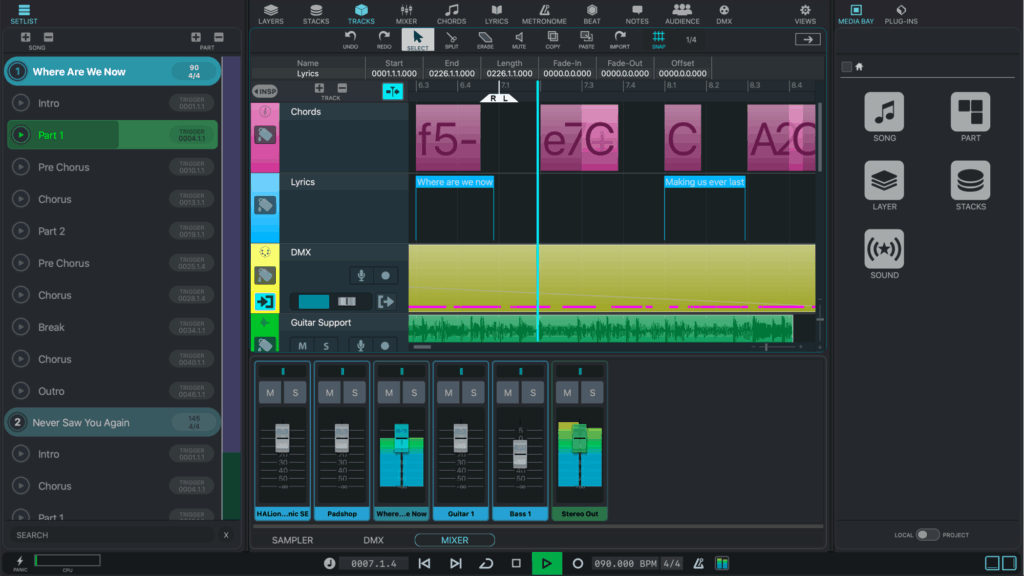

The real breakthrough came in 1989 with the launch of Cubase for Atari ST. Visualized by Wolfgang Kundrus and implemented by a team that included Kracht, Stefan Scheffler, Michael Michaelis, and Charlie—who contributed the M-ROS real-time system—Cubase introduced the now-classic arrange window with horizontal tracks and graphic parts on a timeline.

let’s talk a little bit about the beginnings of 1989. I mean, Cubase was launched in 1989. That’s that’s pretty unbelievable.

Where did the name Cubase come from?

Who whose idea was that?

00:10:19 @charlie

I don’t really know. I know that it was supposed to be it was like cube and bits. So it was supposed to be labeled Qbit, but then the French said that’s not a good word in France. You know?

00:10:41 @Athan Billias M2M

Yvan Grabit is shaking his head. No. Don’t use that word.

00:10:43 @charlie

So we had to change that name, kind of at the last minute.

It was tough. So and then somebody came with Cubase.

Which was close enough. So that’s how it got there.

Charlie Steinberg

Interview with The MIDI Association

Yamaha, Steinberg, and the CBX-D5: An Early Step Toward the DAW

In the early 1990s, the music technology world was shifting from MIDI-only sequencing to the first generation of computer-integrated digital audio recording. Musicians wanted to record vocals, guitars, and acoustic instruments alongside their MIDI tracks—without leaving the computer-based workflow they had developed on platforms like the Atari ST and early Macintosh systems.

This transition set the stage for a groundbreaking collaboration between two industry leaders:

- Yamaha – a global pioneer in digital audio hardware and signal processing.

- Steinberg – an emerging leader in MIDI sequencing software, based in Hamburg.

Their shared goal was ambitious for its time: create an affordable, computer-controlled digital multitrack system for musicians. The result was the Yamaha CBX-D5, one of the earliest hard disk–based digital audio recording units designed to integrate tightly with Steinberg’s software.

So talk a little bit about Cubase Audio and the movement from just MIDI to actually being able to record audio. I mean, originally, every DAW started off as a MIDI sequencer because you just didn’t have the processing power to record audio back then.Right?

00:11:30 @charlie

Right.No way. No way. And the hard disk wouldn’t keep up with that at that time.

It started out with the DigiDesign Audio Engine.

Because they were the only ones who have a hard ware, and they had a kind of an API, but it was a bit tricky because you always had to stop whenever you wanted to do anything. You had to stop the transport. That’s where later our motto became “don’t stop the music”.

It was kind of hitting back against Digidesign. Then what happened was that Yamaha came to us with the CBX-5D, and they wanted us to, to write the software exclusively which was a big deal. They really wanted to do something about the Digidesign stuff and compete with it. And that was great. I think it was a great concept.

Because it was kind of a dumb machine.

It had ADADA and a SCSI port so we could access the disk.

But everything else was left to the software, and

I think it was a great product. Could have done better, but it was our goal and led into our own, Cubase Audio followed by the Falcon.

Charlie Steinberg

Interview with The MIDI Association

Why Yamaha and Steinberg Collaborated

Steinberg’s Need: A Digital Audio Engine

By the early 1990s, Cubase had established itself as a powerful MIDI sequencer, but contemporary computers did not yet have the processing power, storage bandwidth, or dedicated conversion hardware to handle professional-quality digital audio on their own.

To move beyond MIDI, Steinberg needed:

- a dedicated DSP engine for audio,

- high-quality A/D and D/A converters, and

- a reliable way to synchronize audio playback with MIDI sequencing.

Yamaha’s Need: A Bridge Between Hardware Studios and Computers

At the same time, Yamaha was investing heavily in digital technologies: digital mixers, multi-effects processors, and early digital multitrack recorders. Yamaha saw that the future of production would combine:

- dedicated digital hardware, and

- computer-based sequencing and editing.

To reach that future, Yamaha needed a strong software partner with established credibility in the European and global MIDI sequencing market. Steinberg, with Cubase on the Atari ST and Macintosh, was the natural ally.

Together, the companies set out to build a hybrid system where Steinberg would provide the musical workflow and Yamaha would provide the audio engine.

What the Yamaha CBX-D5 Was

The Yamaha CBX-D5 was a compact, half-rack–sized digital recording unit. In essence, it functioned as:

- a 2-track digital hard disk recorder,

- a dedicated DSP engine for audio processing,

- a high-quality A/D and D/A converter, and

- a synchronization device for integrating audio with MIDI sequencing.

Most importantly, it was designed to work hand-in-hand with Steinberg Cubase, and later with Cubase Audio, on Atari and early Macintosh systems. This combination allowed musicians to:

- sequence full arrangements in MIDI,

- record digital audio (vocals, guitars, acoustic instruments), and

- play everything back in sync from within a single software environment.

In practical terms, the CBX-D5 was an early version of what we now think of as an audio interface plus DSP recorder controlled by a DAW.

Division of Roles: Who Did What?

Steinberg’s Contribution

Steinberg’s role in the collaboration was centered on software integration and workflow design. The company:

- developed the drivers and communication protocols needed to control the CBX-D5 from within Cubase,

- integrated the CBX-D5 into Cubase Audio, creating one of the first hybrid MIDI + audio environments,

- provided the arrange window, editing tools, transport, and synchronization controls, and

- ensured that MIDI events and audio playback remained tightly locked together.

Yamaha’s Contribution

Yamaha designed and manufactured the CBX-D5 hardware, including:

- the A/D and D/A conversion stages,

- the internal DSP and digital audio engine,

- the physical interfaces and digital I/O, and

- the firmware for transport control, recording, and playback.

Yamaha brought decades of expertise in digital signal processing, converter design, and hardware reliability to the project, while Steinberg delivered the composition and editing environment that musicians were already using daily.

In modern terms, the CBX-D5 system looked very much like what we now call a DAW + audio interface solution, but at a time when that concept was only just emerging.

Using the CBX-D5 with Cubase

When connected to Cubase or Cubase Audio, the CBX-D5 enabled musicians to:

- record up to 2 tracks of 16-bit, 44.1 kHz digital audio,

- play back audio in sync with multiple MIDI tracks,

- edit arrangements in Cubase while the CBX-D5 handled the audio workload, and

- integrate external microphones, instruments, and line-level sources into a MIDI-based production.

For many users, this was the first time they could combine traditional recording with MIDI sequencing in a coordinated, computer-driven workflow. It represented a major conceptual step towards the fully integrated digital audio workstation.

Impact on the Industry

The CBX-D5 was not a mass-market product in the way later interfaces and native DAWs would become. Factors such as the high cost of hard drives, limited computing power, and the rapid arrival of competing systems (such as Digidesign Pro Tools and Opcode Studio Vision) meant that the CBX-D5 remained a relatively specialized solution.

However, its strategic impact was significant:

- It paved the way for Steinberg’s Cubase Audio, which would later evolve into full DAWs capable of multitrack audio and MIDI on general-purpose computers.

- It strengthened the technical relationship between Yamaha and Steinberg, foreshadowing deeper collaborations in digital audio networking, interfaces, and ultimately Yamaha’s acquisition of Steinberg in 2005.

- It demonstrated that a computer and an external DSP-based audio engine could operate together as a single, integrated production system—a direct ancestor of today’s DAW plus interface paradigm.

Legacy of the Yamaha–Steinberg CBX-D5 Project

Although the CBX-D5 itself is now a historical footnote, the collaboration behind it represents an important early chapter in the story of computer-based recording. It brought together:

- Japanese expertise in digital audio hardware, and

- German leadership in MIDI sequencing and user-focused software design.

In hindsight, the CBX-D5 looks like a prototype of the future: a small, dedicated digital recording and processing box under the full control of a computer-based sequencer. The ideas explored in this collaboration helped set the stage for:

- ASIO and low-latency audio driver models,

- native DAWs that integrate MIDI and multitrack audio, and

- today’s ecosystem of audio interfaces and controller-centric production workflows.

As we look back on the evolution from MIDI sequencers to modern DAWs, the Yamaha CBX-D5 stands as an important milestone—a bridge between hardware-based digital recording and the software-driven production environments that define music creation today. VST and ASIO.

It allows started a long and fruitful relationship with Yamaha that foreshadows the eventual acquisition of Steinberg by Yamaha many decades later.

Steinberg Audio Falcon

The Steinberg Audio Falcon was an early-1990s external digital audio recording and playback system designed to bring hard-disk audio to Atari Falcon computers running Cubase Audio. At the time, native audio recording on personal computers was still in its infancy, and the Atari Falcon—despite its built-in DSP—benefited from dedicated hardware to achieve professional-quality results.

Steinberg developed the Audio Falcon as a tightly integrated solution that provided:

- 2-track 16-bit digital audio recording and playback

- High-quality A/D and D/A conversion

- Low-latency synchronization with Cubase Audio Falcon

- External storage and clocking optimized for audio workloads

The Audio Falcon functioned much like a dedicated DSP/audio interface, offloading the heavy lifting from the Atari while still allowing sample-accurate sync with MIDI sequencing inside Cubase. This combination made the Falcon one of the first widely used hybrid MIDI + audio production systems outside of Macintosh environments.

Although short-lived—partly due to Atari’s market decline—the Audio Falcon played an important transitional role. It demonstrated Steinberg’s early commitment to bringing true digital audio recording into the computer-based workflow, paving the way for later innovations such as Cubase Audio on Mac/PC, ASIO, and VST, which would ultimately help define the modern digital audio workstation.

Cubase Audio

Originally a pure MIDI sequencer, Cubase quickly expanded. In 1992, Cubase Audio added hard-disk recording, blending MIDI sequencing with digital audio long before “DAW” was a common term. The software moved from Atari to Mac and Windows, and by the mid-’90s Cubase had become a global standard in project studios and professional rooms alike.

ASIO and VST

Steinberg’s next leap would define an entire ecosystem. In 1996, as part of the Cubase development, the company introduced Virtual Studio Technology (VST), an open plug-in format that allowed third-party developers to build effects and instruments that loaded directly inside the DAW.

Just a year later Steinberg released ASIO (Audio Stream Input/Output), a driver protocol designed to minimize latency and provide a consistent, low-overhead path between audio hardware and software. Together, VST and ASIO became core infrastructure for the modern music software world; both are still ubiquitous standards today.

So, that brings us to 1996. And probably one of the biggest things that certainly Steinberg and you did which was virtual studio technology.

I mean, that had that pretty much changed the game for everybody.

Was there an impetus behind virtual studio technology? Was there something that happened that triggered you to to focus on VST?

00:14:34 @charlie

Yeah. Most definitely. It started with, again, DigiDesign. So we wrote

three plugins for the DIE System.

And, the other thing was that we were working on QA’s audio and we had those meters. You know? And the meters were like the cassette tape meters. They were like blocks, you know.

And then Frank Zimmerlin came along. He was our graphics guy.

I didn’t know him too well at that time.

Different department. And I said, you know, I I think this is silly because we have all these precious pixels. We should use them to for precise

VU meter displays.

And he did a few graphics for a channel, you know, and also for the plug ins.

And I think he came up with the idea, “this is like a virtual studio

so, let’s call it virtual studio technology”.

I think that’s how it came about.

Charlie Steinberg

Interview with The MIDI Association

Charlie’s fingerprints are all over this era—both as a developer and as a musician constantly pushing for tools that felt musical rather than technical. His work on Pro-16, Pro-24, Cubase, and the first generations of VST helped define how MIDI and audio are handled inside a computer.

Growth, new platforms, and a new home with Yamaha

Through the ’90s, Steinberg expanded into new areas. WaveLab, introduced in 1995, brought professional editing and mastering to Windows users. In 2000 Steinberg launched Nuendo, a DAW focused on post-production, film, and broadcast, and in 2001 the company released HALion, a software sampler that anticipated the modern virtual instrument workstation.

By the turn of the millennium Steinberg employed around 180 people and posted revenues in the tens of millions of Deutsche Marks and later Euros. In 2003 the company was acquired by video specialist Pinnacle Systems, and in 2004 Yamaha reached an agreement to acquire Steinberg outright. Since 2005 Steinberg Media Technologies has been a wholly-owned Yamaha subsidiary, with design and development continuing in Hamburg.

The Yamaha era brought tighter integration between hardware and software. Steinberg developed ranges of audio and MIDI interfaces (UR, MR, CI, and others) while continuing to push its software portfolio.

Honoring a Lifetime of Innovation

Dorico, Cubasis, and Steinberg in the mobile and notation age

As devices and workflows evolved, Steinberg stayed close to the front of the pack. In 2012 the company launched Cubasis, an iOS DAW that brought serious audio and MIDI recording, editing, and plug-ins to the iPad, later expanding to Android. That same year Steinberg opened a London office and hired the former Avid team behind Sibelius to create a new professional notation platform.

The result, Dorico, was released in 2016 and has rapidly become one of the most respected scoring applications in the industry. Together with Cubase, Nuendo, WaveLab, HALion, SpectraLayers, and a broad family of VST instruments, these products define Steinberg’s modern identity: a full ecosystem for composing, recording, mixing, mastering, scoring, and live performance.

In fact, Cubasis 3.7 is up for a NAMM TEC Award at the same 2026 NAMM show Charlie will be receiving his lifetime achievement award.

Charlie Steinberg today

Although he is no longer involved in day-to-day management, Charlie Steinberg has never really stopped building tools. He continues to perform as a keyboardist and has remained active as a software designer.

One recent example is VST Live, Steinberg’s live-performance host, where he has described the origins as a personal solution for managing backing tracks, clicks, and show structure for his own bands.

His contributions have already been recognized by the wider industry; he received a MIPA Lifetime Achievement Award in 2009, and has even been nominated for a Grammy Lifetime Achievement honor. The MIDI Association’s 2026 Lifetime Achievement Award builds on that legacy, specifically honoring his role in bringing MIDI sequencing and digital audio into everyday musical life.

A legacy woven into MIDI itself

From the perspective of the MIDI community, Charlie’s influence is hard to overstate. The very first Steinberg products translated the then-new MIDI protocol into intuitive, tape-style workflows on home computers. With Cubase, Steinberg defined how generations of musicians would see MIDI—piano rolls, arrange windows, controllers, and automation lanes. VST and ASIO opened doors for countless other developers, turning MIDI-capable software instruments and effects into a vibrant global ecosystem.

Today Steinberg remains an active MIDI Association corporate member and a key partner in the broader standards community, recognized on MIDI.org for its creation of industry-standard technologies like VST and ASIO and for its ongoing work as part of the Yamaha family. Cubase 13 and Dorico 5, both released in 2023, show that the company is still pushing forward with new MIDI editing tools, performance workflows, and expressive scoring features.

As the MIDI ecosystem evolves into its next chapter—with expanded expressiveness, new profiles, and new forms of connectivity—it does so on foundations that Charlie Steinberg helped pour: the idea that a musician with an affordable computer, a MIDI connection, and the right software can have a “virtual studio” at their fingertips.

Honoring Charlie at NAMM 2026 is therefore more than a look back. It’s a reminder that the spirit that launched a home-soldered MIDI interface and a 16-track Commodore 64 sequencer in a rainy Hamburg apartment is the same spirit driving today’s innovations in MIDI and music technology: curiosity, practicality, and a deep love of making music.

https://www.steinberg.net/stories/charlie-steinberg-manfred-ruerup